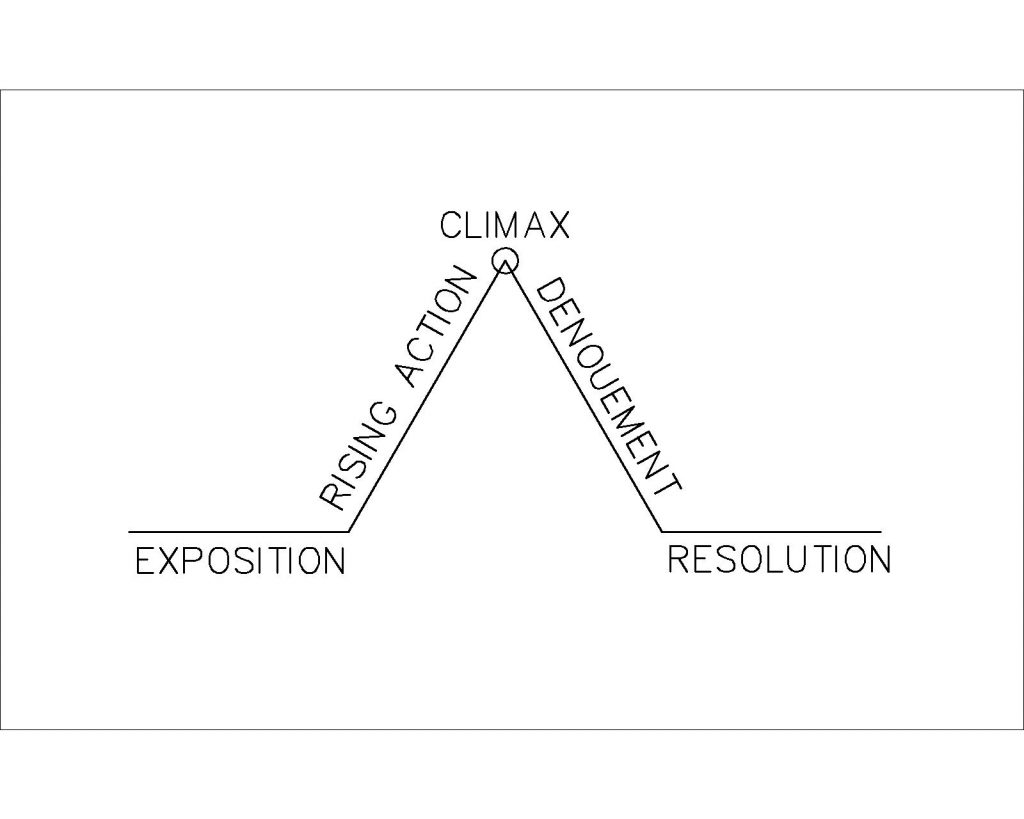

Freytag's Pyramid

In 1863 Gustov Freytag, first known as a playwright and later a novelist, published Die Technik des Dramas. (Released in English much later as Freytag’s Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art.) While his novels reflected some of the ugliness and turbulence of the time in which he was writing, the technique he laid out for understanding dramatic structure has endured.

He modeled this for the stage, dividing the structure into five acts, which are usually graphed Freytag’s Pyramid.

Exposition – Introduces characters and their motivations.

Rising Action – Introduction of conflict.

Climax – The turning point that defines the outcome of the story.

Falling Action – The part where evil seems about to triumph, but good takes the upper hand and wins.

Denouement – Resolution is achieved.

This is usually presented as the most basic plot model for a novel as well, and it graphs pretty closely to how novels were being written at the time. But when you look at the modern novel, does it still make sense to devote an entire act to exposition and one to denouement?

To illustrate this change in structural taste I offer you an opening line from the 1950s, where the author doesn’t want to slow down the beginning – and yet knows previous reader expectation, so the character feels the need to apologize for it. “If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of ****, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.” – J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (1951)

All of the pieces still need to be there – to put it in terms of the hero’s journey, we do need to see a brief glimpse of the character’s ordinary life before he steps through the door to adventure, and we do need to feel that the main plot problem has been resolved when he steps back through to the ordinary world. But you absolutely must hook your reader within the first three pages (agents often don’t ask for any more than that for an initial read), and anything that comes after the climax is by definition anticlimactic.

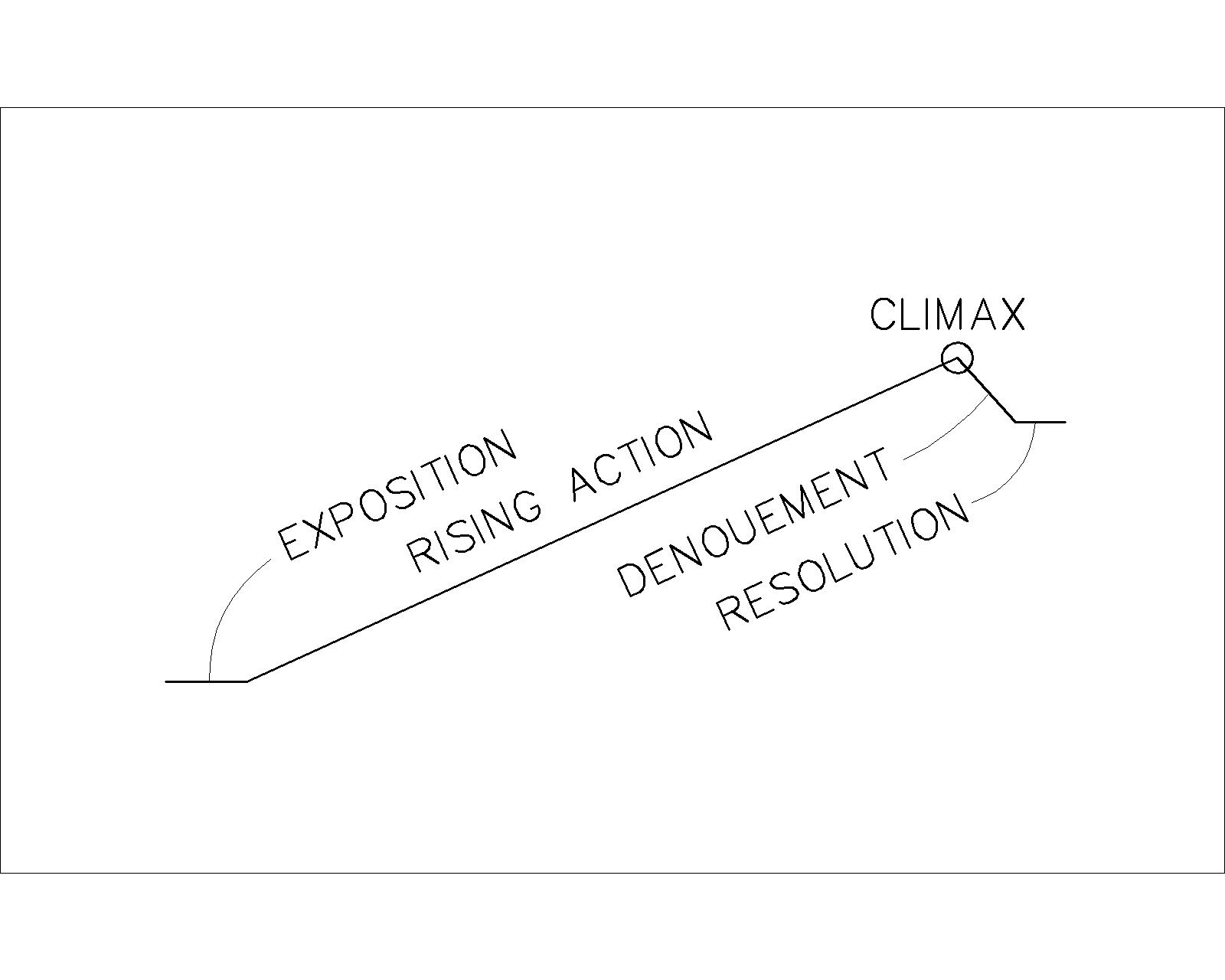

I think it’s confusing to see this laid out as an equal pyramid (where the climax looks like the midpoint), and gives new writers the idea that they have all the time in the world to pad their manuscripts at both the beginning and the end. Graphically, it makes more sense to show it more like a stock market line. Both the exposition and denouement are truncated, and the resolution is brief – or may even be merely implied.

We usually talk about a three act structure for novels these days instead of five, where Act 2 is roughly twice as long as Act 1 or Act 3. (Occasionally this is divided into four acts, with an Act 2A and Act 2B.) This forces you to roll the exposition and the inciting incident together, which makes for a shorter, more exciting opening, and the ending becomes a race to the climax, which is chasing at the heels of the conclusion, rather than a falling away from the excitement.

For a Beat Sheet that uses a 2A – 2 B plot model, and a couple of other ways to graph out your plot, check out these worksheets in the resources section of my web site.